Hiking on the roof of Africa

In the Simien Mountains National Park in the north of Ethiopia, there are more than a dozen four-thousanders crowd. If you hike here, you will experience deep gorges, rugged cliffs and green plateaus. A World Heritage Site with spectacular views.

The most beautiful of the camps is Gich. It lies above the village of the same name on a huge plateau. We share the soft meadow mats at 3500 meters in height with delicate horses grazing above the huts and some children playing frisbee with a young Frenchman.

In front of us is our first four-thousander, the Inatye, with a magnificent view over the entire national park. The first full day of hiking behind us: Six hours we walked on narrow paths through moss-covered forests and knee-high grasses. At the end came the hardest, one last climb over the main street of Gich. We have climbed the steep, rock-cut path in large steps. At the top we enjoy the landscape exhausted, lying down, stretched out in front of our tents.

The umbrella of Africa is called the Ethiopians the Simien Mountains National Park (SMNP), in German Sämen National Park. At just 220 square kilometers, more than a dozen four-thousand-meter crowds throng here. The highest with 4624 meters is the Ras Daschen. More than a thousand feet deep, the volcanic rock breaks off into steep, shady ravines. And the green, sunny plateaus are still inhabited and cultivated at over 3000 meters.

Gardens surround the villages with the thatched rondavels with teff, a millet species cultivated in Ethiopia as a particularly resilient crop. In spring, from September to October, gardens and pastures light up in fresh lime green. In the northeast, a spectacular mountain range around the Ras Daschen completes the panorama.

We are as well-practiced mountaineers with our two children, 7 and 13 years old. For reinforcement we borrowed a Reitmuli. Even our luggage – tents, cooking utensils, food – is brought from camp to camp by a small caravan. Teddy, our young guide from the town of Debark at the foot of the mountains, takes the children by the hand when it gets steep.

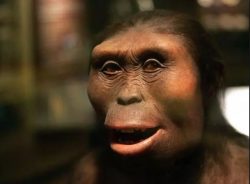

The 21-year-old runs next to us when we’re tired and just looking around, pointing to the Jeladas, a baboon-related monkey species found only here on the plateau. Also a scout with an ancient rifle accompanies us. He says he has always had it. What he needs it remains unclear, but the protection is required by the state.

From a promontory we can observe a wonderful spectacle of nature: In one of the shady gorges of the opposite slope, a waterfall plunges hundreds of meters into the depths. Teddy says that climbers on this wall have been downhill recently. The sighting and securing of the rocks took two days, on the third day the Spanish pioneers ventured into the depths. On the fourth, the descent was possible again via another route. Climbers then reached Camp Gich again via a ladder.

The Ethiopian guides, trained for three years with special knowledge of the mountains and in the English language, guide foreigners to the right places for camping and climbing. The extreme athletes, however, had to bring their own equipment.

Our lunchtime camp is also located at a refreshing waterfall. Several times, cool streams pour into deep catch basins. We scramble over the slate-gray rock, find niches for a comfortable seat and let our feet dangle over the abyss.

Time to look for the Walia Ibex, the Ethiopian ibex. He remains hidden, however, the animals are rarely seen. Not long after the Sämen Mountains were proclaimed a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1978 , they were given the status of endangered heritage: too many people live in the mountains to keep their animal populations growing.

Since then, Unesco and local politicians have fought a fierce struggle for every square meter of space that the National Park is to expand and any village that could lose its livelihood and be relocated.

Our most impressive animal experience in the mountains is therefore closely linked to the people. A few children joke with us at one of the rest areas and lose sight of their real task – the herding of the flock of sheep. Suddenly we see the animals storming over the pasture in an excited zigzag. A little later, the children drag an injured sheep. A wolf or jackal tore it, they tell it. Because of the rabies danger, the farmers can not even consume the meat.

At night it gets cold in the camps. Frost forms on the grass, the Milky Way stretches across the night sky. At the fire in the round hut, stories are being told, dreams spun, plans for the future made.

For the young leaders in the National Park it is the dream of tourist discovery. Because so far, the spectacularly beautiful mountains have remained almost unknown. Nearly 20,000 foreign hikers are currently entering the National Park each year – only a fraction of the number of visitors to other African natural monuments.